Author: Lucien Canton

Crisis Management: Transparency Provides Protection

My colleague, Johnathan Bernstein, recently ended a blog on the Chilean mine rescue with this comment:

Truly successful crisis management does more than simply resolve the issues at hand. By making public the steps being taken to rectify and resolve issues, little room is left for damaging rumor and innuendo to creep in and stakeholders far are more likely to lend a sympathetic ear.

This is probably the most succinct statement of the role of crisis management that I have ever read.

As emergency managers, we tend to sometimes treat information as something that must be protected and doled out piecemeal. Part of this is because for years we've been trained that media is the enemy and forget that they can, in fact, be allies in our quest to get vital information to the public. Many times it's not enough to just do your job – you have to let the public know you are doing it and why you're doing it the way you are. Johnathan's statement reminds us that how well we handle the crisis today can save us considerable agony in the future.

Crisis Communications in the San Bruno Fire

For those readers who have been following the events following the explosion of a gas line in San Bruno, California, last month, it's now possible to access the dispatch communications from that terrible night. Dan Noyes, an investigative reporter for KGO 7, our local ABC affilliate, did an excellent report that captures the confusion and chaos initially faced by responders and how things were brought under control. In connection with this story, he has also posted an MP3 file of the dispatch communications.

The communications record offers a couple of teaching points for those of us who must manage crisis. First, we understand that the first few hours of any crisis is chaotic as we seek to gain information about the event. Sometimes our information is wrong, as were the initial reports in San Bruno that an airplane had crashed. We have to make the best decisions we can with the best available information. We understand this. However, the public does not always understand it. With access to our internal communications a matter of public record, we must be prepared to answer the inevitable questions that will arise after the crisis is over.

Secondly, we sometimes forget that everything we say is being recorded and is subject to review. Inside jokes, gallows humor, or fits of temper are part of how we communicate but taken out of context, they can make us seem callous or incompetent. In this day and age, we need to remember that everything we say on our "internal" communications will be accessible to anyone who wants to review it.

So the next time you key your mike, remember that it's not only operational communication, it's also crisis communication.

Internet Security and the Paranoid Mindset

Ever give much thought to cyber-attack? A lot of us are at least familiar with the concept but would we know one if we experienced it?

As an emergency manager, one of the things I really worry about is the slow-onset disaster – the event that starts low key and progresses so slowly that by the time you recognize something is happening, you're already behind the power curve. Training yourself to anticipate this kind of disaster means you sometimes come across as a bit paranoid.

So what's this got to do with cyber-attack? Consider the following:

- On September 13, Chase bank experienced problems with it's website after software from a third–party database company corrupted information in its systems causing over two days of downtime and affecting millions of customers. Chase stated that this was a technical error.

- On September 17, American Express suffered a systems outage. This was nothing major and the system was soon restored.

So, was this just a coincidence that two major financial institutions suffer outages within days of each other? That's certainly possible. Or is something more insidious going on here?

I guess it really depends on your level of paranoia.

Pacific Gas and Electric another BP?

Many of you I know have been following the recent tragedy in San Bruno, California. This one is a bit personal for me as I frequently drove by the area damaged by the gas explosion, some of the dead were friends of friends, and many of my colleagues are working on the scene, either in their official capacity or as volunteers.

We've reached that stage in disaster response where the shock is wearing off and the finger-pointing is beginning. Pacific Gas and Electric is taking flak for its maintenance procedures and has just been ordered to inspect more than 5,700 miles of pipeline. At this point, they're probably wishing they'd spent more on maintenance.

PG&E is cooperating fully with investigators and has pledged $100 million to help rebuild San Bruno. The pipeline was inspected in March and passed and rumors of complaints about the smell of gas days prior to the explosion do not seem to be substantiated. A portion of the damaged line was scheduled for replacement. This is all good news for PG&E.

However, PG&E is also supporting a proposal before the California Public Utilities Commission that would require customers to pay the uninsured portion of catastrophic fires, such as the one in San Bruno. It doesn't help that a lot of locals recall that PG&E spent about $40 million in the last election to defeat a public power initiative. Both of these are decisions based on the business needs of the company and were in place before the explosion. However, they do not play well with the public and are already beginning to affect PG&E's reputation. If it also emerges that there were corners cut in maintenance or delays in replacing the pipeline because of cost, PG&E may well find it itself in the same position BP did – in the cross-hairs with no place to hide.

Emergency Preparedness – Shifting the focus for emergency management

September is National Preparedness Monthin the United States and Mother Nature is certainly doing her best to remind us of the importance of being prepared. Since September 1st we've seen a hurricane along the East Coast, a tropical storm in Texas that caused tornado watches, and a major wildfire in Colorado. As I write this, another tropical storm is building in the Atlantic. On the international scene, we've experienced a volcanic eruption in Indonesia, a tropical storm in Bermuda, and an earthquake in New Zealand. And the month isn't half over yet!

As an emergency manager, I'm a big supporter of anything that helps motivate people to prepare. However, I'm always a bit concerned when we launch one of these ad campaigns that we are not really making much of a difference. Dr. Dennis Mileti spoke at the International Association of Emergency Managers conference a few years ago and pointed out that a lot of how we try to influence behavior is not consistent with what social science research shows is really effective. Simply put, warnings and scare tactics don't work. People instead will do what everybody else is doing.

Part of the problem as I see it, is that we have made preparedness an end in itself and closely associated it with disasters. We focus on specific plans and kits and train in skills related to disaster. None of this is bad, of course, and I firmly support programs such as community emergency response teams (CERT). However, our approach tends to make preparedness something outside of every day life when it really should be part of how we live our lives. For example, most homes have a flashlight because it has multiple uses, not just because we need it in an earthquake. I'm also willing to bet that the flashlight you use daily works while the one in your emergency kit hasn't been checked since you bought it.

So let's try something a bit different for this National Preparedness Month. Rather than repeating a lot of the same material we always use, let's keep our preparedness advice grounded in the realities of day-to-day life. Let's encourage people to prepare because it helps us deal with daily life.

Preparedness – it's not just for disasters!

Disasters and Social Media

In my July newsletter I briefly discussed the Ushahidi Program as an example of the growing use of social media in disasters using. On August 9, the Red Cross released a survey showing just how important social media is becoming. The results are striking:

- 69% of respondents believed emergency responders should be monitoring social media

- 74% expected a response in less than an hour after a tweet or Facebook posting

- 20% would contact responders through digital means if 911 was not answering

If respondents knew of someone in trouble, they would also turn to social media.

- 44% would ask social media contacts to notify authorities

- 35% would post a request for help on an agency's Facebook page

- 28% would send a direct Twitter message to responders

Another finding that isof interest to emergency managers is that more web users say they get emergency information from Facebook than from NOAA weather radio.

I believe it no no longer matters whether emergency managers choose to take social media seriously. We really have no choice. Our profession is driven, to a large extent, by public expectation. In this case, that expectation is clear – the traditional methods by which we communicate with the public are no longer sufficient.

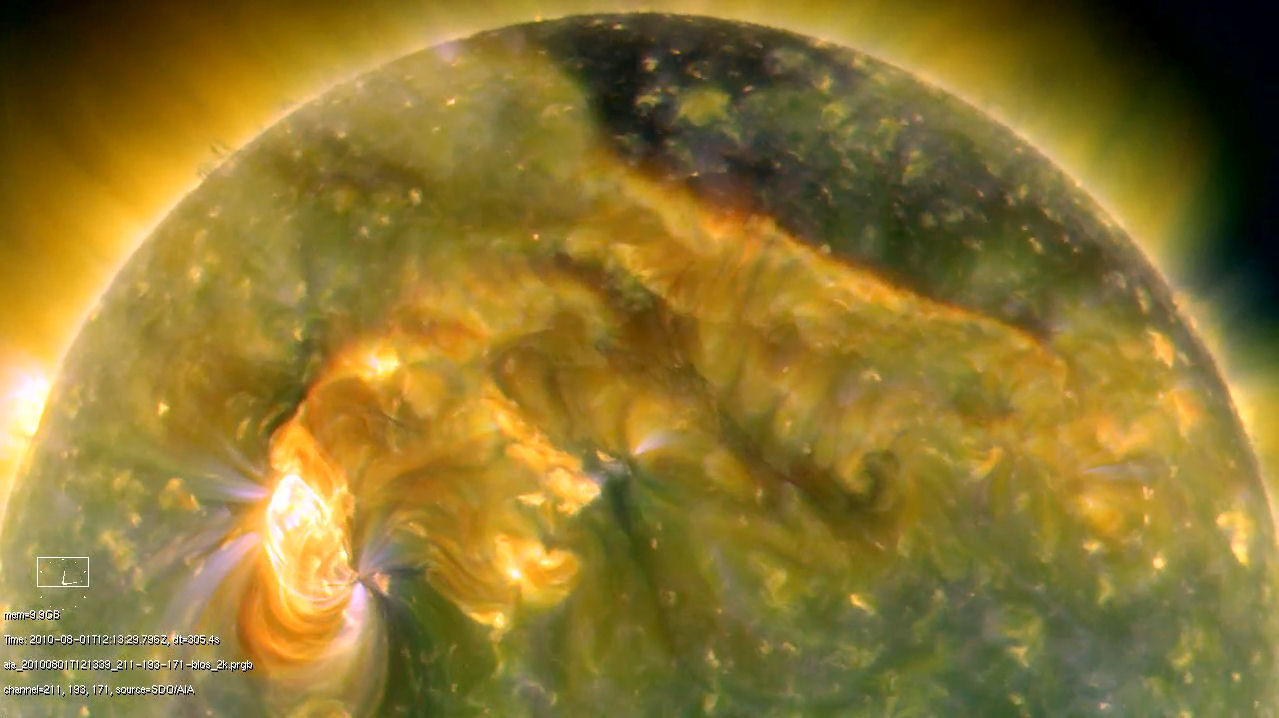

Solar Storms – Do They Matter?

Effective emergency management begins with an assessment of risk. The problem is in identifying hazards and their potential impact on the people and organizations we serve. It seems there's a never ending stream of hazards.

Some of them are not very noticeable. According to NASA, on August 1 there was considerable activity on the earth-facing side of the sun: a C3-class solar flare, a solar tsunami, multiple filaments of magnetism lifting off the stellar surface, large-scale shaking of the solar corona, radio bursts.

The activity also included two coronal mass ejections (CME), one of which sparked a G-2 (on a scale of G-1 to G-5) magnetic storm on earth on August 3 that lasted 12 hours. Sounds ominous but it did little more than spark Northern Lights over Europe and North America. The second is still on the way and, according to NOAA's Space Weather Prediction Center, may produce a major magnetic storm tomorrow.

Here's NASA's definition of a CME:

CMEs are large clouds of charged particles that are ejected from the sun over the course of several hours and can carry up to ten billion tons of plasma. They expand away from the sun at speeds as high as a million miles an hour. A CME can make the 93-million-mile journey to Earth in just two to four days. Stronger solar storms could cause adverse impacts to space-based assets and technological infrastructure on Earth.

So what's my point? As I've said many times, risk is relative. For most of us, solar storms have no discernible effect, beyond putting on a natural light show. However, large scale storms have the capacity to damage power systems, disrupt communications, and degrade high-tech navigation systems. If you work with or rely on these systems, you should at least be aware of the potential impacts of solar storms. Monitoring solar activity might be cheap insurance.

My thanks to my friend and colleague, Regina Phelps, whose blog H1N1 (Swine Flu): If It’s Not One Thing, It’s Another…Solar Tsunami to Strike Earth, inspired this article!