Mythmaking: Turning Fact Into Fiction

If you’ve been following my blog for any length of time, you’re probably aware that I have a penchant for history. I believe history has a lot to teach us and there are common themes that seem to repeat throughout history that have a bearing on current affairs. For example, Barbara Tuchman’s A Distant Mirror: The Calamitous 14th Century takes its title from her premise that the crises of the 14th century were reflected in the late 20th century. Similarly, Heather Cox Richardson’s Wounded Knee: Party Politics and the Road to an American Massacre describes political corruption in the late 19th century that is eerily similar to what we are observing with the current administration.

However, one of the most interesting issues for me has always been the truth behind myths. In many cases, we find that many myths do have a historical basis. The problem is that the facts behind a myth are often altered for a variety of reasons. We must ask ourselves what it is that makes myth so enduring and why do they persist, even when the truth is well known.

Some of variation between reality and myth is understandable and can be put down to misinformation that has changed in the retelling of an event. A myth is often the product of oral tradition, and it may be centuries before it is written down. Consider the classic works of Homer, The Iliad and The Odyssey. Homer is believed to have composed them as an oral recitation some 400 years after the events at Troy and were not written down until over 200 years later.

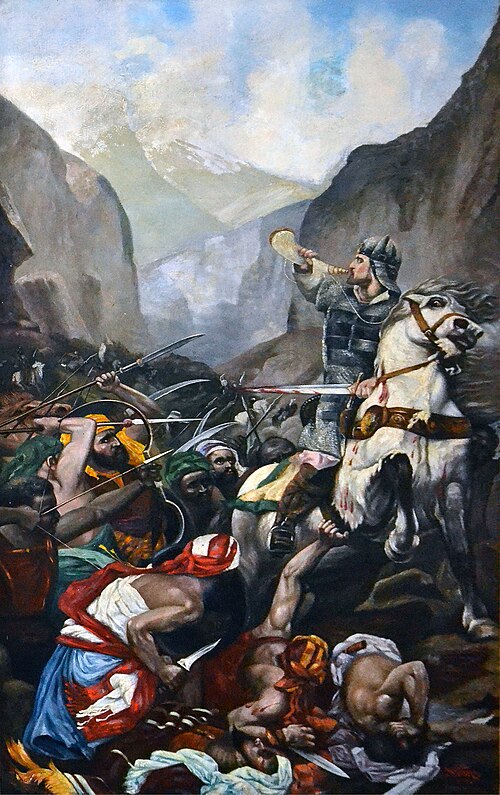

In other cases, events may be deliberately exaggerated to inspire. The Battle of Roncevaux Pass in 875 CE that resulted in the death of the legendary French knight Roland was an ambush of Charlemagne’s rearguard by Basque soldiers in retaliation for his burning of Pamplona. However, the myth changed the Basque to Saracens and had Roland dying heroically, creating one of the most influential myths of the Middle Ages.

Exaggeration can sometimes cross the line into deliberate disinformation, done for political purposes. Nero’s fabled fiddling while Rome burned in 64 CE was propaganda fomented by his political enemies. He was, in fact, heavily involved in coordinating relief efforts. During World War I, British newspapers were instrumental in spreading a false narrative that the Germans had a processing plant that boiled the corpses of dead soldiers to make oil, fat, and soap, dehumanizing the German army and turning public opinion against what was perceived as a brutal enemy.

In addition to misinformation and disinformation, mythmaking also relies on those that create the myths. We’ve mentioned Homer, who may or may not actually existed, but other poets have done their bit. The myth of Paul Revere’s famous “midnight ride” is famous because of the poem written by Henry Wadsworth Longfellow during the American Civil War to inspire patriotism. There were two other riders riding with him that night and a young girl of 16, Sybil Ludington, rode 40 miles, twice the distance of Revere, to bring the warning to the militia of a British attack on Danbury. Horatius defending the bridge at Rome against the Etruscans in 508 BCE might have been just a footnote in history if not for Thomas Babington Macaulay’s famous poem. And what would have become of the charge of the Light Brigade at Balaclava in 1854 if Alfred Lord Tennyson had not written his famous poem?

Our modern world has largely turned away from poetry, but the mythmakers still exist and are even more effective with advent of social media. X recently unveiled a new feature that reveals the location of users and the results demonstrate that mythmakers are still very much with us. According to news stories, a large percentage of high‑profile MAGA and related right‑wing influencers are based outside the U.S. and thought to be foreign actors using social media to try to reshape American society. Here are some examples gleaned from media sources:

• America First, 67,000 followers, Bangladesh.

• Americaman: 15,000 followers, Indonesia.

• American Patriot: 140,000 followers, Chile.

• Dark Maga: 15,000 followers, Thailand.

• IvankaNews: one million followers, Nigeria.

• MAGA & World: 3,000 followers, East Asia and the Pacific.

• Maga Nadine: 390,000 followers, Morocco.

• MAGA Scope: 51,000 followers, Nigeria, while MAGA Beacon is based in south Asia.

• MAGA: 1000 followers, Germany.

• MAGANationX: 400,000 followers, eastern Europe.

This brings us to the third component of mythmaking: the need for people to believe in the myth. Myths are accepted because people want to believe them. Myths frequently mirror beliefs already held by the recipient, what psychologists call confirmation bias, or speak to emotions that resonant strongly with the recipient. In addition, constant repetition of disinformation creates what psychologists call the illusory truth effect, where the constant repetition of a statement makes it more likely to be believed as true. This is why changing peoples’ minds with facts really has little success when a myth has taken hold. There will always be those who are not prepared to surrender closely held beliefs. For the rest, the only leverage we have is to go after the source: the misinformation or disinformation that is at the root of the myth.